My research interest is death in the Middle Ages, and for my thesis I’m considering looking at the ways death is personified. Right now I’m using a wide range of texts because I haven’t figured out if I am a late or early medievalist, but hopefully I will figure that out as I find more examples. For this blog post, I’m looking at “The Death of Baldr and Hermod’s Ride to Hel” from The Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson (translation by Jesse Byock); “The Pardoner’s Tale” from The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer; and Sir Orfeo from the Auchinleck Manuscript. All of these texts have a character who challenges Death, according to the model of games, which ultimately results in Death winning.

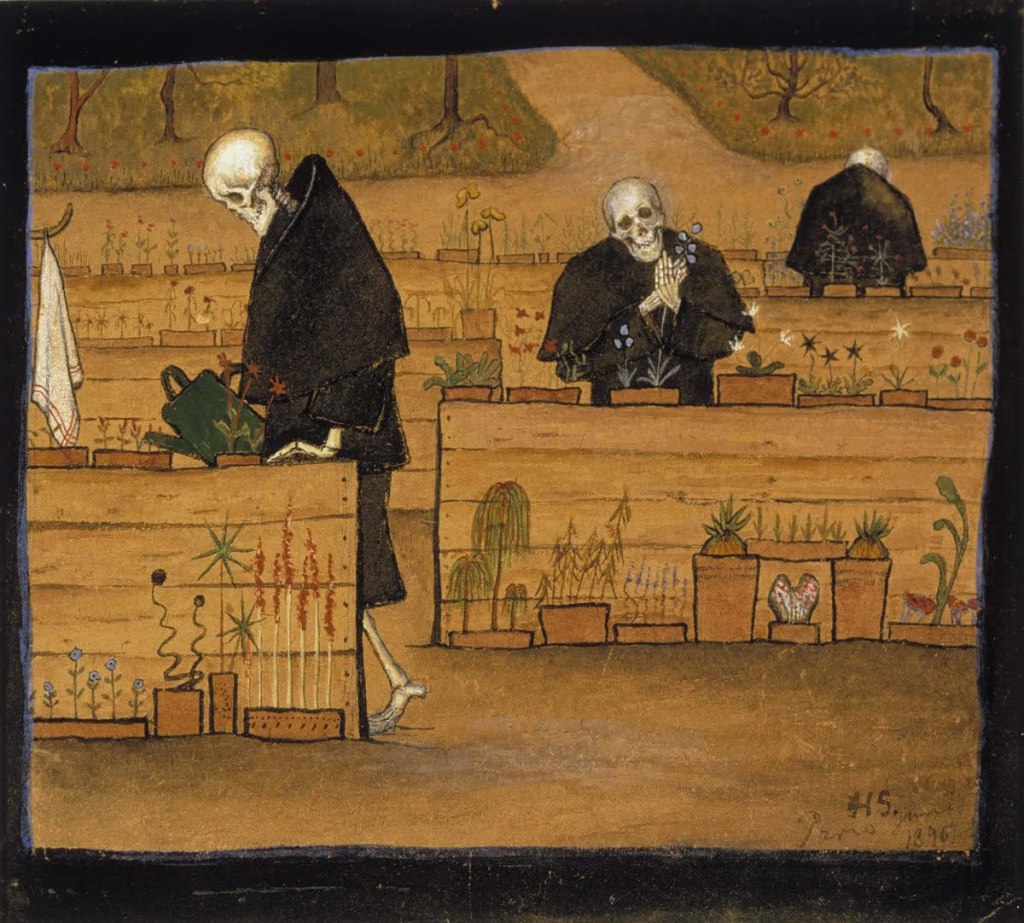

In mythology death personified takes two main forms: A character who causes death and collects a soul or a psychopomp escorting the soul to the afterlife with no control over the occurrence. My definition includes both of these ideas, but also includes anything playing the role of Death. The late fifteenth-century vaulted fresco of “Death Playing Chess” in Täby Church, Sweden — and my background writing narrative for video games— prompted me to consider ways that Death is playing a game. While definitions of “game” very from text-to-text on game studies, the common threads are that they must have rules, autonomy, known outcomes, and goals within a feedback system. The goal is a specific outcome that the player is trying to obtain by subscribing to a set of rules that limit the method of achieving such. When developing a game, the player must have autonomy, as in, there’s a sense of free will. Likewise, game needs known outcomes, which are quantitative or qualitative ways to measure the results that are clear to the player.

In Snorri Sturluson’s collection of Norse myths, The Prose Edda, Hel is the personified figure of Death. Her role as a god is to preside over the realm of the same, and in “The Death of Baldr and Hermod’s Ride to Hel,” she has control on who can come and go from her hall. At the start of the poem Baldr dies and Odin, knowing that his son’s death is the first part of Ragnarök, requests that someone goes to Hel and bribe her for his return. This encompasses both the goal and the known outcome for the game: retrieve Baldr or failure means ruin for the Æsir. The game is defined when Hermod asks to take Baldr back to Asgard and “Hel answered that a test would be made to see whether Baldr was as well loved as some say: ‘If all things in the world alive or dead, weep for him, then he will be allowed to return to the Æsir. If anyone speaks against him or refuses to cry, then he will remain with Hel” (Sturluson & Byock 68). Everything has the choice to weep, and exercising her free will, Thokk the giantess declines and “let Hel hold what she has” (Sturluson & Byock 69). Therefore, in Hermod’s failure to meet the “win conditions” Hel set, death personified won this game.

“The Pardoner’s Tale” of The Canterbury Tale by Geoffrey Chaucer is a narrative of three revelers who upon hearing of their friend’s demise, decide to seek out and kill Death. Serina Patterson even points in her dissertation that the Pardoner’s aim with his tale is to “[warn] his fellow pilgrims of the dangers of gambling”, (Game On: Medieval Players and Their Texts 40). The text is meta in the fact there is a critique of the greed of gamblers, but also, they test their luck in trying to kill Death. Personified Death is omnipresent in “The Pardoner’s Tale” because the revelers never actually physically find them; although some interpret the old man, who gives directions to where Death was last seen, is actually Death themself. Death is still present because when the revelers reach the tree, they find the pile of gold for which they kill each other over trying to gain possession. This text is different than The Prose Edda in that it is an unspoken game, but it still follows the framework outlined before. The goal is to kill Death, but like any good gamemaster, Death gives the revelers a strategic distraction by presenting them with a pile of gold. From the revelers’ perspective, the game has changed. They all want to take the gold for themselves, and the rules are to achieve such without letting the others know. The sense of autonomy is shown by all of them individually deciding to kill the others for the whole pile, which is a clear quantitative result. As mentioned before, the tale ends with the revelers killing each other, and that is how Death wins the game. Death’s strategic distraction, keeps the revelers from killing them, and Death instead comes for their lives. “The Pardoner’s Tale” can be summarized that the revelers sought out Death, and found it.

Sir Orfeo from the Auchinleck Manuscript, is the Middle English retelling of Orpheus. The Faerie King is personified death in this text, who takes the protagonist’s love to his castle in an Otherworld, or the underworld. Sir Orfeo is in self-induced exile mourning the loss of Herodis for ten years before winning her back. In this text the game isn’t realized until they’re in the middle of it. Sir Orfeo sets his goal to retrieve Herodis when he sees her among the faerie-band, but knows that he must hide is true motive to avoid joining the macabre scene at the castle. He enters the Otherworld under the guise of a minstrel, and plays so beautifully the Faerie King grants his whatever he wants. He asks for the woman under the ympe tree (Herodis), and when the king denies him, Sir Orfeo uses the king’s words (or his rules) against him: “as ye syd nouþe,/ What Ich wold aski have Y schold,/ And nedes þou most þi world hold” (lines 466-9). The Faerie King concedes, since he must keep his word, and Sir Orfeo brings Herodis back to life. While Sir Orfeo wins the game in this moment, Death (the Faerie King) still is untimely the winner because the poem concludes with the end of the lovers’ long life. One can presume the pair would then be returned to Death’s domain.

The texts mentioned above all have characters who challenge Death, and play a game with them according to game studies’ idea of “game”. While the details of each exchange differ, Death is ultimately the winner in these encounters. This sampling shows the continued desire to defy Death, even though dying is still an unavoidable concept. My further research into death personified can go in multiple directions: finding more example of Death’s games, looking at other common threads of how death is personified, or considering Death’s role as the adversary. While I don’t know which way I’ll go, it’s certain that games with Death are rigged since everything must end; therefore, when challenging Death, the house always wins.

Works Cited

Benson, Larry Dean, editor. “The Pardoner’s Tale.” The Riverside Chaucer, by Geoffrey Chaucer, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 196–202.

Byock, Jesse L., translator. “The Death of Baldr and Hermod’s Ride to Hel.” The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology, by Snorri Sturluson, Penguin Books, 2005, pp. 65–69.

Patterson, Serina Laureen. “Game on: Medieval Players and Their Texts.” T. University of British Columbia, 2017.

Treharne, Elaine M., editor. “Sir Orfeo.” Old and Middle English: c. 890 – c. 1400: an Anthology, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, pp. 550–563.

I am SO curious to know if anyone has ever beaten Death’s game! Curious that the phrase is “cheating” Death, too — another allusion to a game?

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was so interesting!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m interested in how different texts handle chance so I really enjoyed reading this.

I like that you put a choice about which way to go at the end of a post about games.

I also like Death’s reaction of mild surprise in the Fables panel.

P.S. Cool pictures!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love this so much and am so happy you were able to connect these two interests! You manage to add another layer to death, taking it farther than what many people think of or expect of/from death. I cannot wait to see what you do with you thesis!

LikeLiked by 1 person