To study death is to also study life, because whether it is through fate or fertility, the two are directly linked. My introduction to figures of death was watching Hercules as a child, and learning about the Greco-Roman deities of Hades and the Fates. The movie made it clear that Hades has no control over life and death and it is the Fates who are spinning the life tread or cutting it. The combination of life and death was furthered for me when I learned of Persephone, who is not only the queen of the underworld, but also a goddess of vegetation and fertility. As my interest in death embodied continued, I found that figures of death and life truly are, the cliché, “two sides of the same coin.”

Figures in charge of fate are also found in the Germanic tradition with depictions of the Valkyries and Norns. The Old Norse word valkyrja literally translates to “chooser of the slain” and bear the half dead heroes who die in battle to Valhalla. They clearly have the role of being psychopomps in Norse myths, but Snorri Sturluson furthers their intermixing with fate in that “they are sent by Odin to every battle, where they choose which men are to die” (45). In this way the Valkyries are Death watching over the battlefield, establishing who will die and carrying their souls off. One of the Valkyries is also the youngest of the three Norns, the Germanic embodiment of fate. The Valkyries get to specifically chose who dies in battle, but it is the Norns who “[lay] down laws, they [choose] lives for the sons of men, the fates of men” (Voluspa 21). They make these choices at everyone’s birth, one of which is the length of life.

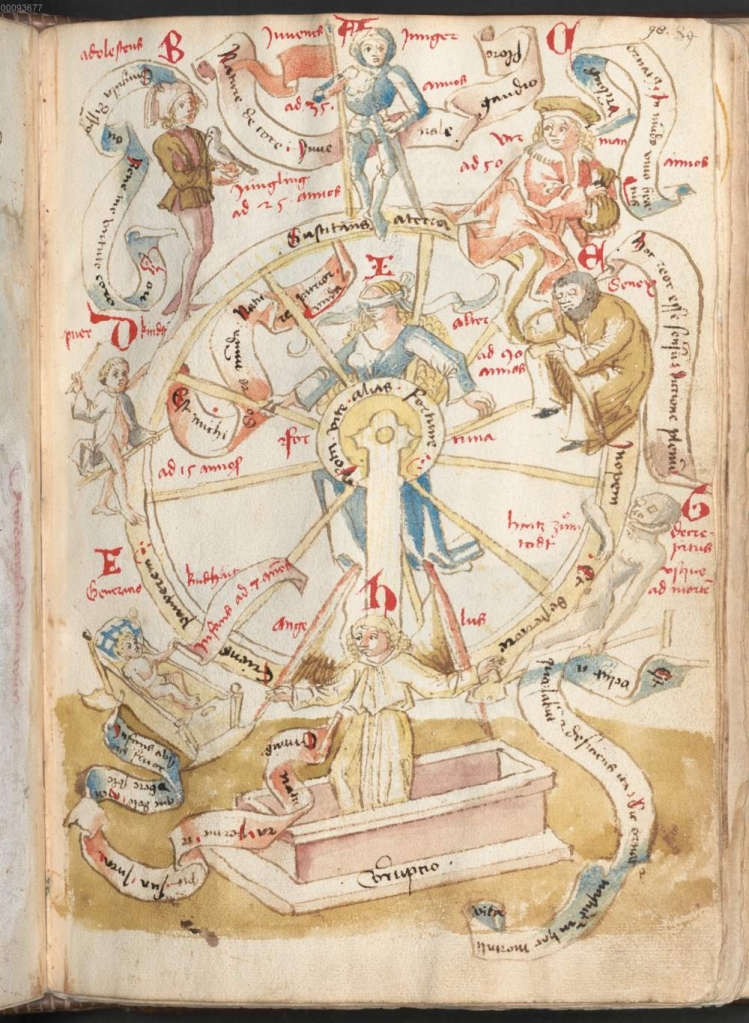

The Middle English motif of Lady Fortune is also in control of fate because of the ups and downs of life at the turn of her wheel. Lady Fortune, like the Norns, is present throughout a person’s life as she follows people from the cradle to the grave. One of the example of Lady Fortune I’ve encountered this year is in the Alliterative Morte Arthure Part IV. In a text mostly removed from the magical and otherworldly elements typically found in the Arthurian tradition, a figure of Death is still present when Arthure dreams of Lady Fortune spinning her wheel. Upon the wheel in this dream are the Nine Worthies, one of which is Arthure himself. It’s a nonverbal omen that shakes Arthure to his core: “And when his dredful dreme was driven to the ende, / The king dares fore doute, die as he sholde” (3224-25). Fortune is always spinning and it is his tine to take the turn towards the grave, just as the other eight worthies have on the wheel. If people get on the wheel at birth, the Lady Fortune is a figure of life and death as she takes each person through growth and decay.

Going back to the Nordic texts, it’s easy to forget about Freyia’s hall, Folkvang, where she houses “half the slain she chooses every day,” the other “half Odin owns” in Valhalla (Grimnismal 14). The existence of this hall where Freyia presides over the dead, makes her another embodiment of death. This role is in contrast to her role as the goddess of fertility. Kel in their blog post “How to Love Your Monstrous Mom: Thoughts on Acker’s ‘Horror and the Maternal in Beowulf'” brought to my attention the concept that a mother gives us life but also death. Their work in this area perfectly illustrates the image of Freyia in that she is both a giver of life and a keeper of death, and that the roles are not mutually exclusive.

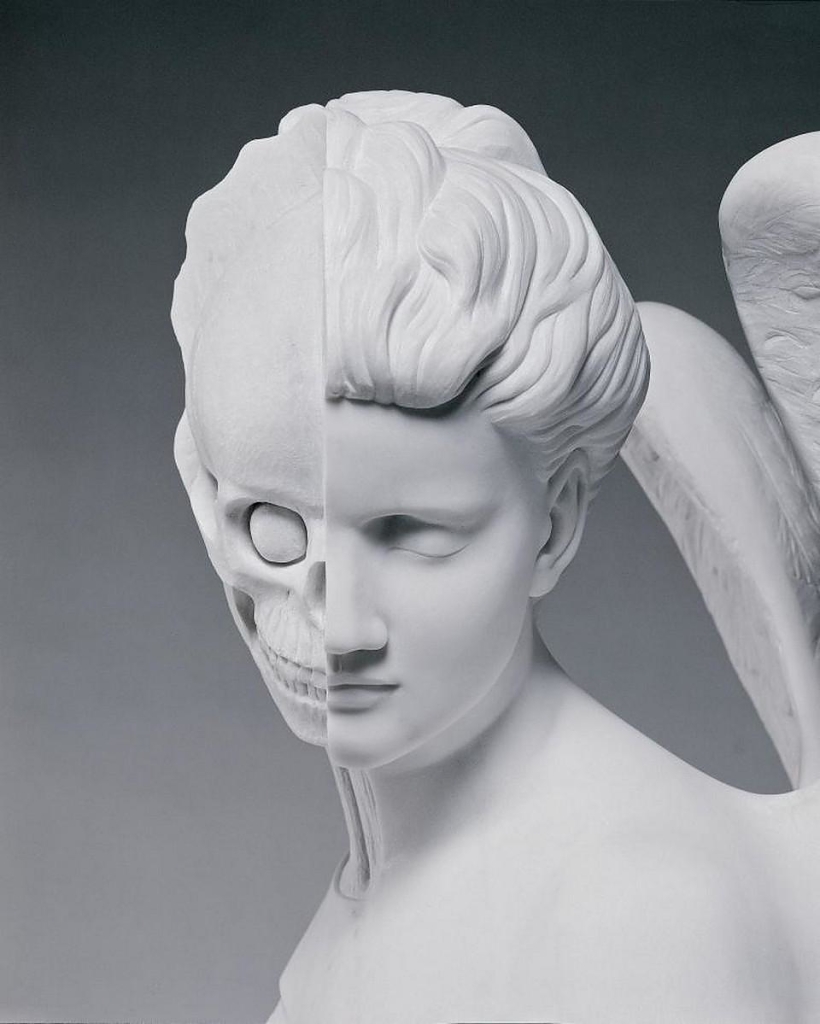

Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd.

Hel, the Norse goddess of death, also illustrates the blurring of life and death in Snorri’s description of her image: “She is half black and half a lighter flesh colour and is easily recognized. Mostly she is gloomy and cruel” (39). The side referred to as “black” is often interpreted to be a skeletal image in the state of decay, making her visually appear as the point the two states of being are meeting. Hilda Roderick Ellis discusses supernatural women and their connections to death in the book The Road to Hel, and such is a place for further study for me. I’m especially interested to look more in-depth at Baldrs draumar and the dead seeress that Odin calls up from the ground. The seeress also exists on this boundary by being dead, and being drawn back to life for knowledge of Baldr’s fate.

The earth is another point where life and death meet. The tradition in Middle English of earth to earth, is entirely based around the idea that life comes from the earth, and will be return to it upon death. Nature itself is a major motif when talking about the dead because of its role in decay; however, it is also associated with growth and fertility, which is exemplified in the figure of Mother Nature. It is interesting to note that all the figures mentioned above are feminine, or, at the least, described with female pronouns. James J. Paxton observes that personifications are innately female, and anything else is the deviant (“Personification’s Gender”). In my research it is only figures of death with connections to fertility or fate that are exclusively female. Further research will involve looking at why medieval literature reserves that dual identity for figures of femininity.

Sources:

Benson, Larry Dean. King Arthur’s Death: the Middle English Stanzaic Morte Arthur and Alliterative Morte Arthure. Western Michigan Univ., 2005.

Caciola, Nancy. Afterlives: The Return of the Dead in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press, 2017.

Chism, Christine. “King Takes Knight: Signifying War in the Alliterative Morte Arthure .” Alliterative Revivals, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, pp. 189–236.

Clements, Ron and John Musker, directors. Hercules. Walt Disney Pictures, 1997.

Ellis, Hilda Roderick. The Road to Hel: A Study of the Conception of the Dead in Old Norse Literature. Greenwood Press, 1977.

Guthke, Karl S. The Gender of Death: A Cultural History in Art and Literature. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge;New York;, 1999.

Knowlton, E. C. “Nature in Middle English.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 20, no. 2, 1921, pp. 186–207.

Larrington, Carolyne, translator. The Poetic Edda. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Menton, Kel. “How to Love Your Monstrous Mom: Thoughts on Acker’s ‘Horror and the Maternal in Beowulf’.” þaes Wyrmes Wyrd, 30 Oct. 2019, https://wyrmeswyrd.wordpress.com/2019/10/30/how-to-love-your-monstrous-mom-thoughts-on-ackers-horror-and-the-maternal-in-beowulf/

Morey, James H. “The Fates of Men in Beowulf.” Source of Wisdom: Old English and Early Medieval Latin Studies in Honour of Thomas D. Hill, by Charles Darwin Wright et al., University of Toronto Press, 2007, pp. 26–51.

Paxson, James J. “Personification’s Gender.” Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, vol. 16, no. 2, 1998, pp. 149–179.

Robinson, Fred C. “God, Death, and Loyalty in The Battle of .” Old English Literature: Critical Essays, by Roy Michael Liuzza, Yale University Press, 2002, pp. 425–444.

Sturluson, Snorri, and Jesse L. Byock. The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology. Penguin, London, 2005.

Tristram, Philippa. Figures of Life and Death in Medieval English Literature. Elek, London, 1976.

One thought on “Life: The Harbinger of Death”